Get the Popular Science daily newsletter💡

Breakthroughs, discoveries, and DIY tips sent every weekday.

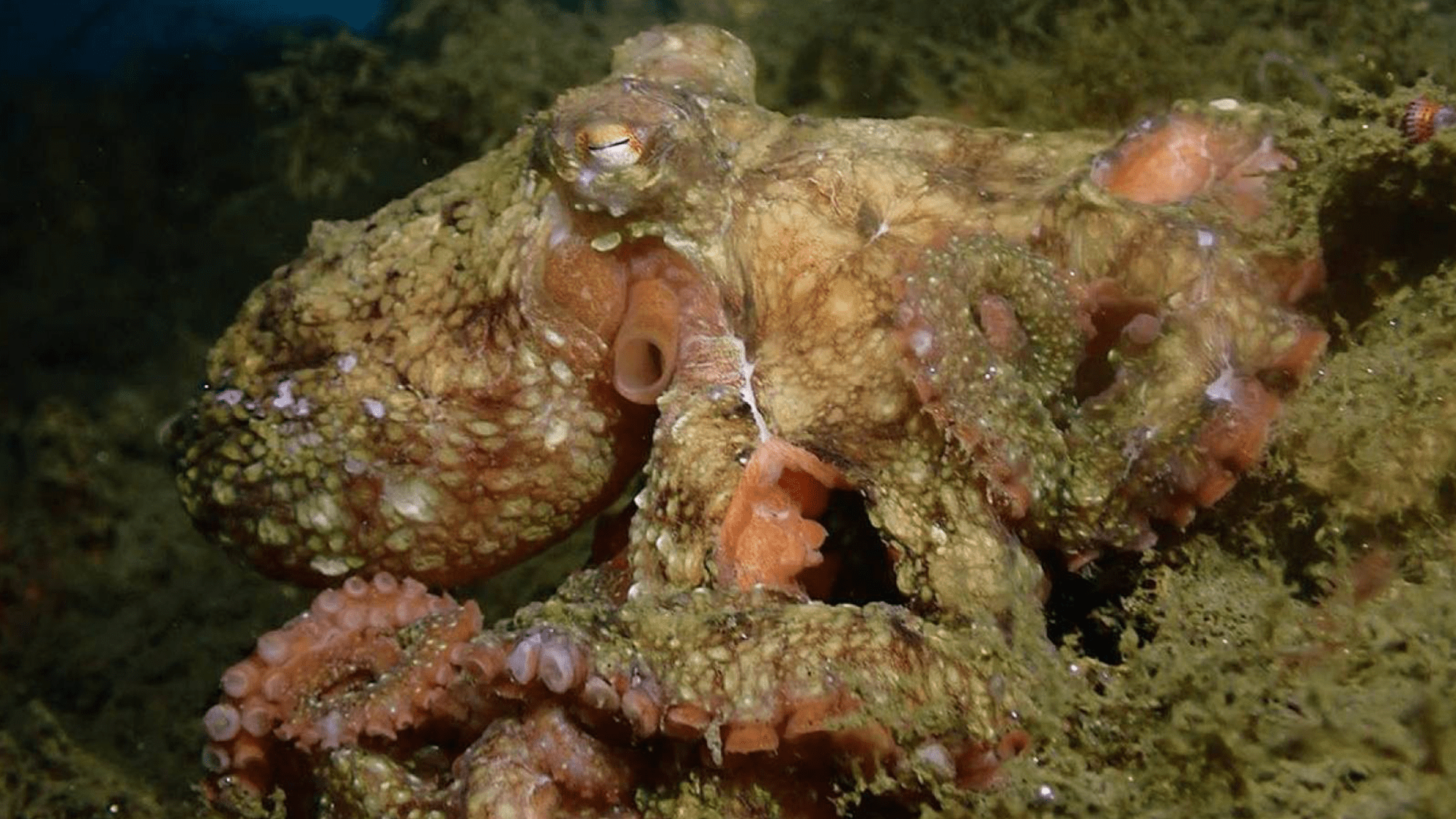

Cephalopods like octopuses, squid, and cuttlefish have the mesmerizing ability to change the color of their skin to camouflage into the surrounding environment. Multiple biological processes involving a natural pigment called xanthommatin drives this unique ability. As such, various industries are interested in using xanthommatin in products such as paint and natural sunscreen, but the pigment has been hard to research. Harvesting xanthommatin from animals isn’t very efficient, and traditional lab methods are laborious and low-yielding.

Now, a team of researchers has found a way to produce up to 1,000 times more xanthommatin than previous approaches—by making a single bacterium do it. While that might sound like overkill, the achievement has significant implications for a broad range of areas, from animal biology and chemistry to cosmetics and the military.

“We needed a whole new approach to address this problem,” Leah Bushin, chemical biologist and natural products chemist at Stanford University, said in a statement. Bushin is lead author of the study recently published in Nature Biotechnology. “Essentially, we came up with a way to trick the bacteria into making more of the material that we needed.”

[ Related: Octopus arms are the animal kingdom’s most flexible.]

Usually, microbes resist using their essential resources to create something unfamiliar without really manipulating their genes. To solve this, Bushin and her colleagues linked xanthommatin production to a bacterium’s survival. Namely, they started with a genetically engineered bacterium that could only live if it produced xanthommatin and another chemical called formic acid, which fuels the cell’s growth. The dynamic is essentially a self-sustaining loop—if the bacterium doesn’t produce xanthommatin, it doesn’t grow, Bushin explained.

“Large quantities of a previously rare material like xanthommatin allows scientists to explore its properties in a host of ways as an antioxidant, pigment or color-changing material in many types of products,” Bradley Moore, senior author of the study and a marine chemist with joint appointments at the University of California San Diego and Scripps Oceanography, tells Popular Science. “We are already exploring opportunities with a cosmetic company and are exploring other practical applications such as in paints and sensors.”

According to the team, the United States Department of Defense has also expressed interest. The study’s authors also argue that their method could work with other chemicals, possibly helping industries transition from fossil fuel-based materials to nature-based alternatives.

“As we look to the future, humans will want to rethink how we make materials to support our synthetic lifestyle of 8 billion people on Earth,” Moore concluded in the statement. “Thanks to federal funding, we’ve unlocked a promising new pathway for designing nature-inspired materials that are better for people and the planet.”

2025 Holiday Gift Guide

Don’t settle for a gift card again this year. Our list of editor-approved gifts suit every personality and budget.